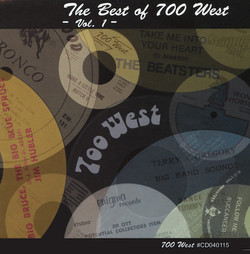

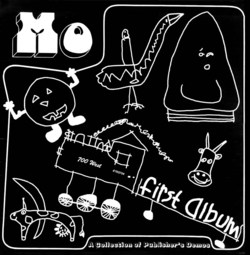

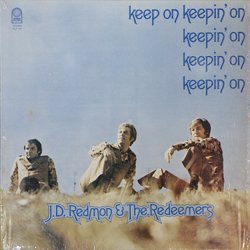

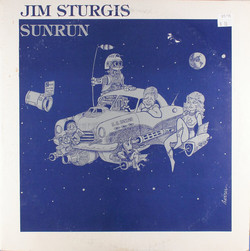

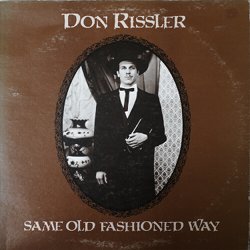

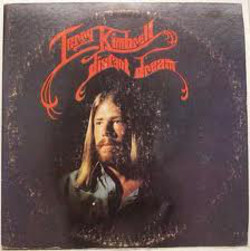

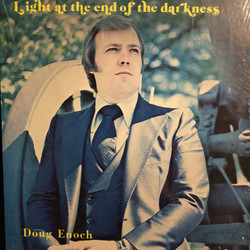

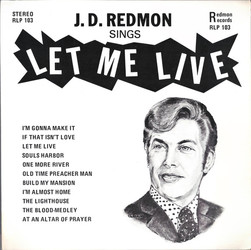

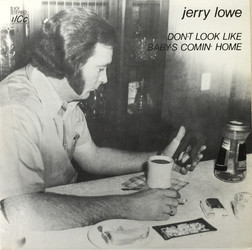

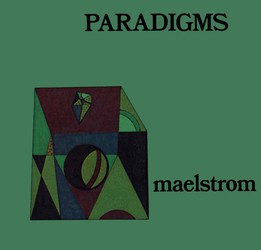

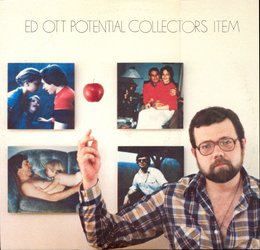

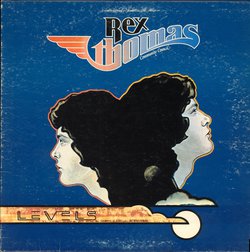

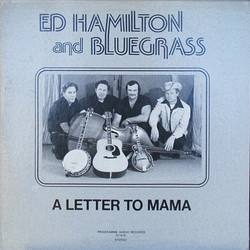

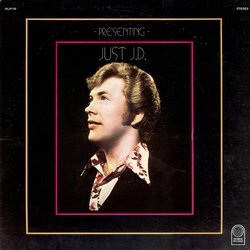

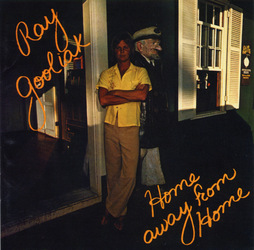

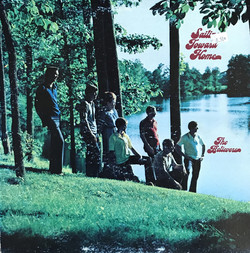

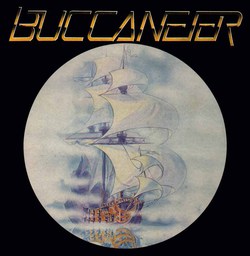

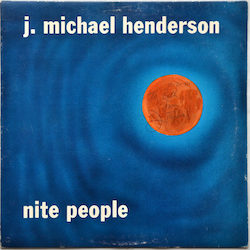

<< The Albums >>

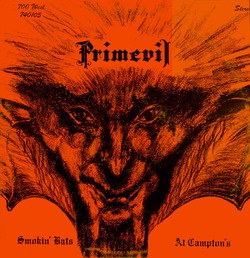

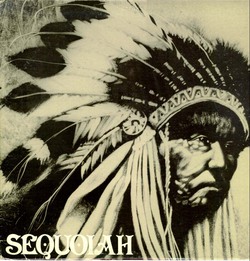

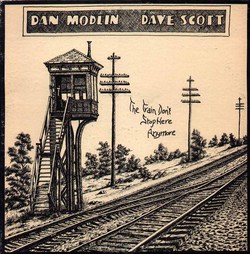

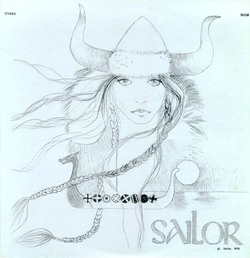

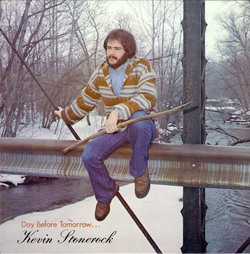

Between 1972 and 1983, about 35 singles and 37 albums were recorded by Mo Whittemore at the 700 West Recording studio. A select few were released on the 700 West label. Others were released on other labels. Today, these are highly-collectible records!

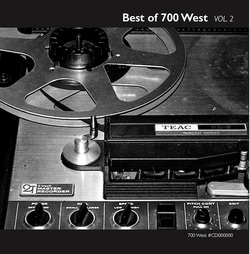

We're currently working to digitize the original 1/4" master and 1/2" source tapes that remain in the 700 West archives.